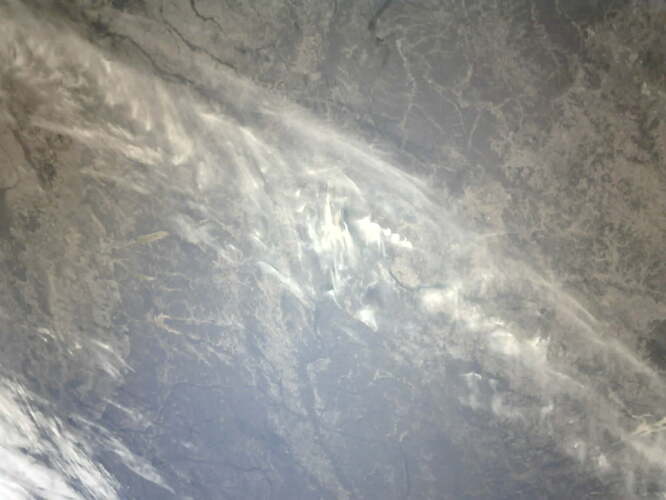

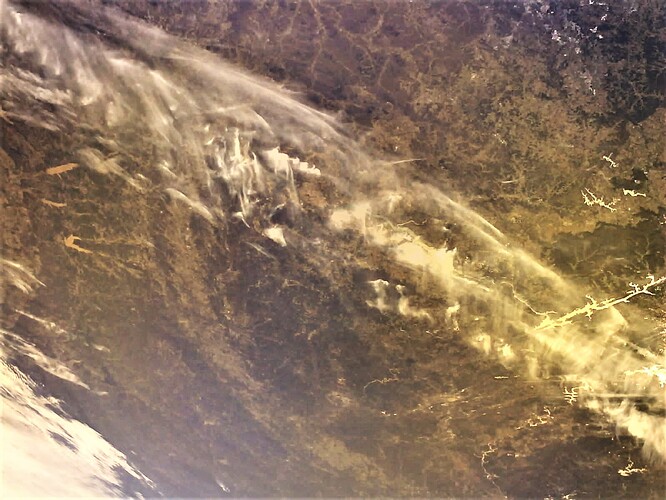

A visible (top) and near-infrared (bottom) image pair showing middle Tennessee and Northern Alabama.

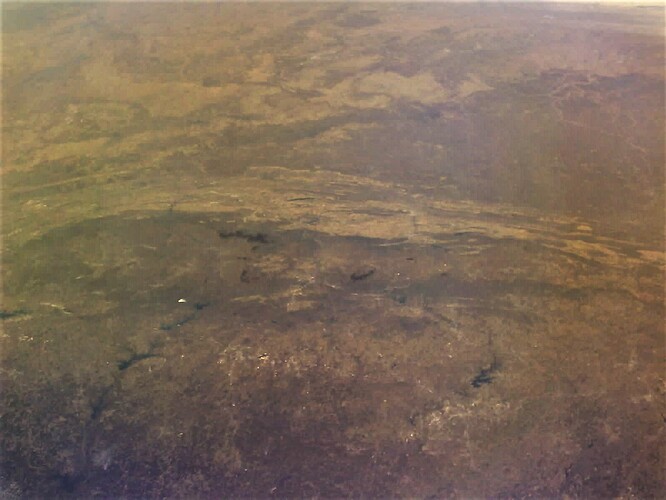

A similar view as the two images above, but looking a little further to the south, deeper into Alabama (near-infrared camera). These three images of the southeastern U.S. have not yet been corrected for atmospheric haze and glare - we’re working on that now.

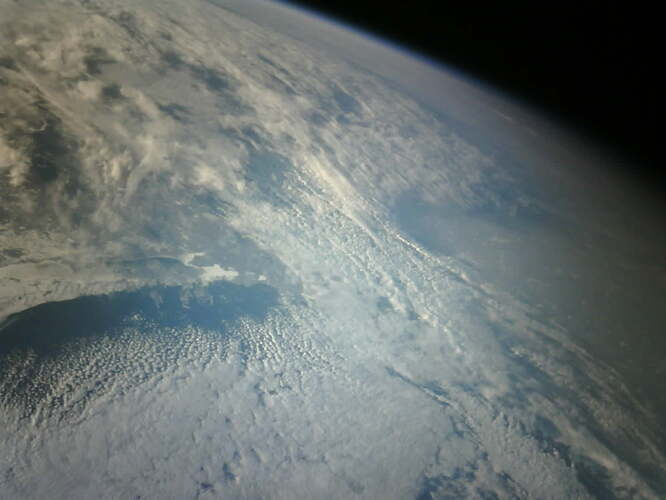

One more image for today - not quite sure yet what this shows, but it has some lovely depth in the cloud layers, and a fine view of the terminator. This might be looking at the Gulf coast, or maybe the South Atlantic coast of the U.S. (Georgia or South Carolina? Let us know if you see something familiar!)

Thank you @pethornton for sharing all these with the community. And the images are wonderful. We will repost/reshare some on the SatNOGS social media. ![]()

They are worth sharing with the world. ![]()

This looks wonderful. Did you got this via SatNOGS or via your own ground-station setup?

Thank you, @Nikoletta , we’re happy to have these shared!

@elkos thank you! These were mainly received at our ground station, but we are sometimes able to fill in missing packets from SatNOGs observations.

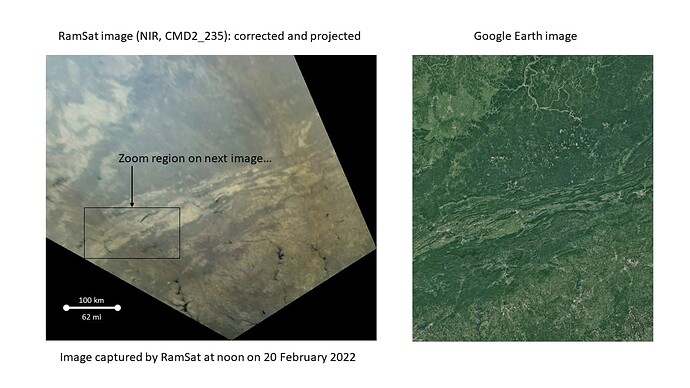

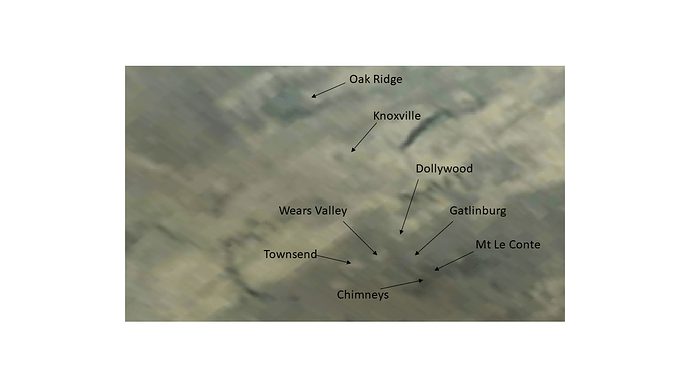

The RamSat team has been working to downlink several more images, and to apply atmospheric corrections to some of our previous images. The first two images below are also special ones for us - they are our first views in visible and near IR of the target geography for our mission, the Great Smoky Mountains and the region affected by the devastating fires that burned through the town of Gatlinburg in 2016. These image were captured on February 20 at about noon local time, and just recently downlinked. The second pair of images are atmospherically-corrected versions of images that I posted in the last update.

We have been able to do some geolocation and image projection on images captured in February 2022, and are able to zoom in and see for the first time our local geography from space! The viewing angle was not great, and we are still trying to get a more nadir-looking view. Note that in the first image below, the view on the right is from Google Earth to be able to assess geolocation. In the second image below, the 2016 fires burned most of the area between the markers for “Chimneys” and “Gatlinburg”. The burn scar is visible in these images, but just barely.

In addition to the images over east Tennessee, we also have some new views with global perspective. We haven’t been able to geolocate these yet, but they are nice to look at… The first two are visible and NIR images of the same scene, with a nice view of the terminator. Maybe looking north into Canada? The third image is the first time we have captured both good curvature of the horizon and the sun in the same image. All images were from late February 2022.

@yb8xm - wanted to thank you for tracking RamSat at your station near Ambon, Indonesia. We have very few observations from the southern hemisphere, and it is interesting to see how the elevation changes during that part of the orbit. Sending you kind regards from Oak Ridge, Tennessee, United States.

RamSat is alive and well - below is the latest benefit that we have received from connection to SatNOGS. (This is copied from my facebook feed, where I try to maintain minimal assumptions about technical expertise)

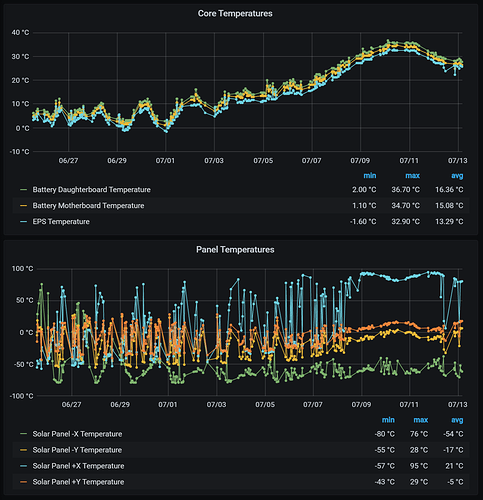

Near the summer and winter solstices, our satellite goes through an orbital configuration that has it experiencing continuous sunlight for multiple days at a time. The technical term is “high beta angle”, and after 13 months in orbit, RamSat has just gone through its third such episode.

One consequence of the intense continuous sunlight is that the solar panels covering 5 of the 6 faces have the potential to get very warm. If the tumbling motion of the satellite is around an axis that is more or less parallel to a line between the Earth and Sun, then one panel tends to face the sun all the time, and it can get very roasty. At the same time, the panel on the opposite side faces continuously into the coldness of space, and it can get very chilly.

With no time spent in Earth’s shadow during this period, and no opportunity for the whole satellite to cool down by radiating away its heat, the temperatures measured on electronic components inside get quite warm, too.

In the charts below you can see temperatures measured in and on RamSat over the past few weeks. The first plot shows interior temperatures (in Celsius) for three different components. The lower plot shows temperatures measured on each of the four large solar panels over the same period. Peak temperatures happened over the past 3-4 days.

Interior temperatures maxed out around 36 C (97 F). That sounds pretty hot, but it’s not so bad cause it’s a dry heat ![]()

The tumble is such that the “+X” solar panel is facing the sun continuously, and it hit a peak of 95 C (203 F). During that same period, the “-X” panel on the opposite side, facing into space, was sitting at about -60 C (-76 F). A very impressive temperature gradient of 155 C (279 F) across a 10 cm (4 inch) structure.

That’s life in space! RamSat is made of tough stuff, and built to take these extremes.

I’m noticing numerous attempts to uplink commands to RamSat, showing up as RamSat responses in the downlink activity at station " 2550 - USU GAS Yagi Az+El", for example as in this recent observation:

SatNOGS Network - Observation 6215378

I’m wondering if @usugas has information on this activity? It’s good to know that the security system for command and control is working, but I’m concerned about the frequency of attempts. We have license restrictions for uplink due to the imaging system onboard (a NOAA regulation). We can discuss entering into a trusted relationship with additional ground stations, but unfortunately we didn’t isolate the security for imaging and other command and control functions, so we need to be careful to not violate our agreement with NOAA. Cheers!

That’s really not good… here is another one ![]()

https://network.satnogs.org/observations/6215376/

I mean, come on! Hacking a student satellite??

I am also wondering how the person was able to figure out the uplink frequency and the protocol…

By the way, is there an email I could write to for the “trusted relationship” stations? I am on the east coast and would like to become one ![]()

Thank you!

I think I know the answer but just to confirm, this activity and responses can not happen with random noise, right?

@fredy, that’s right. The uplinks need to arrive as properly formatted AX.25 UI packets to make it through the radio interface and into the command handler in the flight code.

As far as I understand, the attacker needs to know the correct string to be formatted inside the AX.25 packet… which makes it even more puzzling. And, in case that wasn’t enough, the attacker needed to figure out the right frequency, but I assume that wouldn’t be too hard as I’d expect it to be around 436MHz (close to the downlink frequency).

It seems such that the attacker got past all of these problems. The only thing that is stopping him from controlling is the security key… which I assume is sent with every command. If not, though, once mission control activates the satellite by sending the security key, but does not start sending commands, then the attacker could, theoretically, pretend to be mission control himself and send his own commands.

@pethornton Any thoughts on this?

@jupitersaturn09 the uplink frequency does need to be known, and we do not advertise it. As long as the AX.25 packet is valid, and long enough, our code will attempt to process as a command and report via downlink if there is an invalid security key in the command. Early efforts evidenced in the downlinks at this station show attempts that had packets that were too short. Seems pretty clear that someone was trying a variety of command formats.

@jupitersaturn09 the “hijacking” scenario you describe is not possible with our system.